Matan Asulin, 30, was working at Latet, the organization that operates Israel’s largest food bank, when an elderly woman called him and asked for a home-cooked meal for Sabbath dinner.

“She asked for the basics, maybe some meat or a piece of chicken,” Asulin tells ISRAEL21c.

The pain in her voice broke his heart. After work that day, he went to a nearby supermarket, bought a cooked meal from his own money, and delivered it to her.

“She lived all alone, she had no kids, and she reminded me of my grandmother,” Asulin said. “It really upset me to think about my own grandmother having to ask for food.”

The next day, Asulin shared the story with Ronnie Lee, 26, a woman he had met at Reichman University, where they both studied entrepreneurship and business administration.

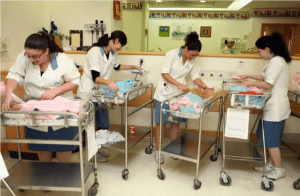

They talked about what they could do to help the more than 100,000 elderly people living in poverty in Israel, many of whom are Holocaust survivors. Asulin and Lee had an idea.

If people were already cooking dinner for their families on Friday for the Sabbath, would it be so much more difficult to make a little extra and then deliver a home-cooked meal to a needy elderly neighbor?

Without wasting any more time, the two friends launched a pilot program called “Heart to Plate” for Rosh Hashana in 2020, asking volunteers in Haifa to cook an extra meal. They served 60 needy elderly people.

A few weeks later, during Sukkot, more volunteers joined in, and they helped 250 people. The volunteers said they were eager to continue, while the elderly recipients told Asulin and Lee that this was the “best thing that ever happened to them.” Better, a few of them said, than any pills they take against depression.

A sense of community

In August 2021, Heart to Plate became a registered nonprofit. Asulin and Lee, who could have gotten jobs in high-tech, have taken on the organization as their full-time employment.

Heart to Plate now has 400 volunteers who have cooked and served more than 8,500 meals to 160 people in five cities around Israel. They are presently operating in Haifa, Kiryat Ata, Migdal Ha’Emek, Rehovot and Yokne’am, and are now expanding the program to other cities.

“The connection between the volunteers and the needy grows from food to having a sense of community,” Lee said.

“I couldn’t believe that a woman my grandma’s age would have to sell her jewelry to buy food.” Ronnie Lee of Heart to Plate

Some of the volunteers have started to take the elderly for medical checkups; others have invited them for Sabbath dinners. One volunteer brought his children to play chess and checkers with a 90-year-old man who rarely goes out.

Lee explained that they set up Heart to Plate so that four volunteers form a team who help one or two people living alone. This way, each volunteer only has to cook one Friday each month.

“A support group is easier because you’re sharing the responsibility,” Lee said.

‘You’re not alone anymore’

The two Heart to Plate founders have enlisted help from companies like Applied Materials, as well as the Haifa Foundation and their alma mater, Reichman University. It also gets help from the US-based Good People Fund.

Asulin said that the organization has reached out companies so their employees can team up, and to youth groups so that teenagers and their families can get involved in helping the needy.

Lee said that she and Asulin both grew up in families where their grandparents were an inseparable part of their lives. She described how sad she felt the first time she visited a needy woman in her 80s who lived alone with her disabled son, in his 50s, in a “tiny apartment that was more like a shed.”

“I couldn’t believe that a woman my grandma’s age would have to sell her jewelry to buy food,” Lee said. “After I met her, I told her, ‘You’re not alone anymore.’”

Heart to Plate has drawn volunteers from a variety of backgrounds to work together. The team that brings homecooked food to Raisa Usbitsky, 80, a Holocaust survivor, includes two Ethiopians, one religious Jew and one secular Jew.

Usbitsky said that after her husband passed away, she “suddenly found herself alone without friends.” Then she signed up with Heart to Plate.

“A lot of people visit me every week,” Usbitsky said. “They are now like family to me.”

Evie Litwok in New York’s Central Park with her Maltese, Ali. Photo by Jeff Eason for LGBTQ Nation

Evie Litwok in New York’s Central Park with her Maltese, Ali. Photo by Jeff Eason for LGBTQ Nation Evie Litwok and her mother, Genia, strolling down Broadway and 151st Street in New York City, a few years after Genia escaped the Holocaust and arrived in the city. Photo courtesy Evie Litwok.

Evie Litwok and her mother, Genia, strolling down Broadway and 151st Street in New York City, a few years after Genia escaped the Holocaust and arrived in the city. Photo courtesy Evie Litwok.