Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. inspired generations of Americans to fight for what is right…to do the hard work of making the world a better place…to do tikkun olam. In honor of Martin Luther King Day, Rabbi Pont sat down with Naomi Eisenberger, founding executive director of The Good People Fund. Don’t miss a chance to hear about this unique organization making a massive impact across the US and Israel.

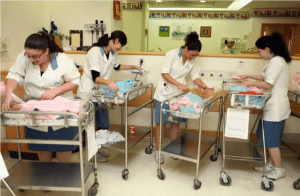

Heart to Plate volunteers cook Shabbat meals for elderly

Matan Asulin, 30, was working at Latet, the organization that operates Israel’s largest food bank, when an elderly woman called him and asked for a home-cooked meal for Sabbath dinner.

“She asked for the basics, maybe some meat or a piece of chicken,” Asulin tells ISRAEL21c.

The pain in her voice broke his heart. After work that day, he went to a nearby supermarket, bought a cooked meal from his own money, and delivered it to her.

“She lived all alone, she had no kids, and she reminded me of my grandmother,” Asulin said. “It really upset me to think about my own grandmother having to ask for food.”

The next day, Asulin shared the story with Ronnie Lee, 26, a woman he had met at Reichman University, where they both studied entrepreneurship and business administration.

They talked about what they could do to help the more than 100,000 elderly people living in poverty in Israel, many of whom are Holocaust survivors. Asulin and Lee had an idea.

If people were already cooking dinner for their families on Friday for the Sabbath, would it be so much more difficult to make a little extra and then deliver a home-cooked meal to a needy elderly neighbor?

Without wasting any more time, the two friends launched a pilot program called “Heart to Plate” for Rosh Hashana in 2020, asking volunteers in Haifa to cook an extra meal. They served 60 needy elderly people.

A few weeks later, during Sukkot, more volunteers joined in, and they helped 250 people. The volunteers said they were eager to continue, while the elderly recipients told Asulin and Lee that this was the “best thing that ever happened to them.” Better, a few of them said, than any pills they take against depression.

A sense of community

In August 2021, Heart to Plate became a registered nonprofit. Asulin and Lee, who could have gotten jobs in high-tech, have taken on the organization as their full-time employment.

Heart to Plate now has 400 volunteers who have cooked and served more than 8,500 meals to 160 people in five cities around Israel. They are presently operating in Haifa, Kiryat Ata, Migdal Ha’Emek, Rehovot and Yokne’am, and are now expanding the program to other cities.

“The connection between the volunteers and the needy grows from food to having a sense of community,” Lee said.

“I couldn’t believe that a woman my grandma’s age would have to sell her jewelry to buy food.” Ronnie Lee of Heart to Plate

Some of the volunteers have started to take the elderly for medical checkups; others have invited them for Sabbath dinners. One volunteer brought his children to play chess and checkers with a 90-year-old man who rarely goes out.

Lee explained that they set up Heart to Plate so that four volunteers form a team who help one or two people living alone. This way, each volunteer only has to cook one Friday each month.

“A support group is easier because you’re sharing the responsibility,” Lee said.

‘You’re not alone anymore’

The two Heart to Plate founders have enlisted help from companies like Applied Materials, as well as the Haifa Foundation and their alma mater, Reichman University. It also gets help from the US-based Good People Fund.

Asulin said that the organization has reached out companies so their employees can team up, and to youth groups so that teenagers and their families can get involved in helping the needy.

Lee said that she and Asulin both grew up in families where their grandparents were an inseparable part of their lives. She described how sad she felt the first time she visited a needy woman in her 80s who lived alone with her disabled son, in his 50s, in a “tiny apartment that was more like a shed.”

“I couldn’t believe that a woman my grandma’s age would have to sell her jewelry to buy food,” Lee said. “After I met her, I told her, ‘You’re not alone anymore.’”

Heart to Plate has drawn volunteers from a variety of backgrounds to work together. The team that brings homecooked food to Raisa Usbitsky, 80, a Holocaust survivor, includes two Ethiopians, one religious Jew and one secular Jew.

Usbitsky said that after her husband passed away, she “suddenly found herself alone without friends.” Then she signed up with Heart to Plate.

“A lot of people visit me every week,” Usbitsky said. “They are now like family to me.”

Candles of Hope: Helping Israelis affected by pregnancy, infant loss

Elysa Rapoport gave birth to a stillborn daughter in August 2016.

In her native Australia, she would have found grief support and information through Red Nose. In the UK, she could have turned to Sands. In the US, organizations such as NechamaComfort, which supports Jewish families and communities through pregnancy loss, infant loss and miscarriage, would have been ready to help.

In Tel Aviv, there was nothing.

“It was terribly traumatic. I couldn’t find what I needed, neither through the hospital nor my health fund. I received one-on-one counseling, but I was looking for a support group,” she says.

Nine months later, her health fund informed her about a support group in Rishon Lezion. Although she found the meetings helpful, Rapoport felt this service should have been available immediately and closer to home.

So she and her mother, Sydney-based early childhood teacher Rebecca Dreyfus, spent the next year-and-a-half working to establish Candles of Hope (candlesofhope.org.il/), a national nonprofit group offering support, information and education to Israelis affected by pregnancy and infant loss.

Their efforts were assisted by Joey Gelpe of Jerusalem, whose second daughter arrived stillborn in 2017.

“We really felt the lack of support and understanding from many parts of society, including the medical establishment,” Gelpe says.

“I felt I wanted to change that as much as I could. The main groups available were for women and I wanted something more holistic. When I heard Candles of Hope was being established, I asked to join the board. At the time I didn’t realize how important it would be.”

Candles of Hope was officially registered in 2019 as a kind of one-stop-shop where bereaved families and healthcare professionals can find existing resources, and where gaps are filled by providing new services.

Its name refers to memorial candles and to the healing power of hope.

“Candles of Hope is an information resource in Hebrew and English – and we want to add Arabic, French, Amharic and Russian to cater to all sectors of Israeli society, because we’ve had approaches from all different communities,” says Rapoport, now the 38-year-old mother of two preschoolers.

“We have a database on our website that lists professional services and support [including English-speaking therapists and counselors], centralizing the information for the first time. There are support groups for men, women and couples, available online, in person or one-on-one,” she adds.

“We are in touch with all the hospitals and health funds, and we lobby the Knesset and Ministry of Health to improve professional training and care at every point along the medical journey of pregnancy loss.”

Despite her limited Hebrew, Dreyfus recruited board members such as Prof. Danny Horesh of Bar-Ilan University’s psychology department, whose research in 2018 found that pregnancy loss can trigger post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Although PTSD research in Israel has tended to focus on combat soldiers, Horesh studies how it affects parents of stillborn infants, who account for approximately six of every 1,000 deliveries.

Horesh was among the speakers at Candles of Hope’s first half-day conference in May 2021, which drew 120 online participants. Sadly, Dreyfus passed away shortly before this event she had worked so hard to actualize.

“My mum and I started this together and I continue this work in her honor and memory,” Rapoport says.

The second annual conference, also online to be as accessible as possible, is planned for May 26. The presentations, mostly in Hebrew, will address aspects such as the complex process in the hospital for both the family experiencing the loss and the medical staff; different forms of grief therapy including writing and visual arts; and learning from the work of international support organizations.

“They have a wealth of knowledge we can benefit from, models we can adopt. We have much to learn from them,” says Rapoport.

“We also collaborate with organizations here in Israel that touch on this topic. We do not want to double up on things already happening, but rather bring them together so that people know about them and can access them.”

Before the formal establishment of Candles of Hope, its board was involved in developing a policy that was approved by the Health Ministry and the Knesset, calling for each hospital to appoint someone to deal with stillbirths.

However, says Rapoport, “Nobody is accountable to make sure it’s happening, and in reality it varies from hospital to hospital. We continue to hear stories about unsatisfactory experiences. We are actively lobbying the Knesset for more accountability.”

SHE GAVE a few examples of situations that need improvement.

One issue is that the mother often is placed in the maternity ward with other moms and newborns. The gynecology department would be a more considerate choice, says Rapoport.

Another issue is that before discharge, the woman is required to register the baby’s birth with National Insurance and get a certificate documenting the stillbirth. Rapoport says this hospital procedure is insensitive to women who suffered a stillbirth.

After discharge, these women have no reason to go to the Tipat Chalav baby health clinics, which is where new mothers are routinely screened for postpartum depression.

“A woman who’s gone through a stillbirth falls into a black hole because she’s not in that system. There is no formal mental health follow-up,” says Rapoport. “We are recommending that a screening survey be given to women through their health fund.”

Perhaps the most serious problem is how parents are presented with their rights in terms of the infant’s burial. They receive a form in Hebrew that explains their options: letting the Chevra Kaddisha (burial society) take care of the whole procedure; being notified and included in the burial; being notified only where the baby is buried; or taking the entire responsibility into their own hands, which is preferred by Muslim and Christian families, says Rapoport.

“People are not always given the form, or they’re given it at the wrong time when they’re too overwhelmed to deal with it. And even if they do choose an option, they don’t necessarily get what they request,” says Rapoport. “To this day I don’t know where my baby is buried although I requested that option.”

She notes that the ITIM Jewish Life Advocacy Center is helping bereaved parents get information from the burial societies, but there is no standardization of procedures.

Gelpe says the improvements “can start from small things, like a bit more sensitivity and understanding at the hospitals’ maternity wards. A child who was stillborn is still someone who died.”

He handles many of the administrative tasks for Candles of Hope, aiming to help bereaved families get connected with existing organizations or find someone to talk to who had a similar experience.

And, he says, “we are helping raise awareness about infant loss and pregnancy loss in a society that encourages having lots of children.”

While many services focus only on bereaved mothers, “the men’s experience is on our agenda,” adds Rapoport. Her own partner, she says, “felt sidelined, invisible to the system.”

Candles of Hope cosponsored a men’s retreat and is in touch with another organization that will be providing a hotline for men until its own hotline is set up.

“We have men reach out to us and we provide them with support services. As an organization, we recognize that men experience the loss too. One of our board members, Nurit Glazer Chodick, did her PhD on the fathers’ experiences,” Rapoport adds.

Candles of Hope has never done formal fundraising; it receives support from private donors and from the US-based Good People Fund.

“The fact that Elysa and her family chose to embrace a subject that brought them loss and deep pain, and turn that into a positive force that is changing society is extraordinary,” says Naomi Eisenberger, founder of the Good People Fund, which supports those engaged in tikkun olam (repairing the world) in Israel and the US.

“For far too long, the needs of women who have experienced the loss of an infant or pregnancy were either ignored or treated with little sensitivity. Candles of Hope is changing that reality,” Eisenberger says.

The War With Russia Is Reviving Past Traumas for Ukraine’s Vulnerable Holocaust Survivors

In late February, four days after Russia invaded Ukraine, Inna Vdovichenko, a staffer in the Odessa office of the Jewish humanitarian organization JDC, was sitting in Natalia Berezhnaya’s home when an air raid alert began. Sirens blared. For Vdovichenko, who had come over to keep Berezhnaya company and to see if she needed food or medications, it was the second time she’d heard such sirens; the noise brought with it a wave of fear. But for Berezhnaya, 88, a Holocaust survivor, there was also a feeling of déjà vu.

“She said, ‘I was a little girl when I had to go to the basement and hide from the bombings over Odessa in 1941, and I can’t imagine going there again,’” Vdovichenko, recalls by Zoom.

Berezhnaya had a home care worker, provided by JDC’s network, by her side, and the two made tea and served chocolates and sang to pass the time and lift the mood until Vdovichenko felt safe to leave.

“These people have to go through the war for the second time in their lives,” Vdovichenko says of the Holocaust survivors she has been monitoring as Ukraine has been rocked by war over the last few weeks. “They are afraid of being left without food, without electricity, without water and [of being] alone, that’s what they fear.”

When Nazi Germans invaded Ukraine in June 1941, the country then boasted Europe’s largest Jewish population, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Scholars estimate that about 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews were killed, by Nazis as well as by collaborators, during the Holocaust. When Nazis shot to death more than 33,000 Jews at a ravine called Babyn Yar in Kyiv on Sept. 29-30, 1941, it was one of the largest mass shootings of World War II. (Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky is Jewish; his family lost relatives in the Holocaust, and his grandfather served in the Soviet Army, fighting the Nazis.)

Berezhnaya is one of Ukraine’s 10,000 Holocaust survivors. Check-ins like the one provided by Vdovichenko have become a vital lifeline for some of the country’s most vulnerable citizens: Among that group, 6,500 are receiving home care and 588 are in the “most disabled” category, according to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), which provides compensation to Holocaust survivors and funds humanitarian relief organizations in Ukraine. Already there have been casualties as well. On March 18, Borys Romanchenko, a 96-year-old survivor of Buchenwald concentration camp, was killed when Russians bombed his apartment building in Kharkiv. “Survived Hitler, murdered by Putin,” Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba tweeted.

Greg Schneider, executive vice president of the Claims Conference, says the imminent danger facing those thousands is forcing his organization to revisit what it means to provide aid to Holocaust survivors.

“Generally, survivors are living in the United States and Israel, in Canada and Australia, in places that are stable,” he says. “[The war in Ukraine] has forced us to do things that we’ve never done in our past, like sourcing pallets of wholesale food, renting trucks, bringing them in across borders. That’s not something we normally do; we’re normally funders.”

The Claims Conference has helped coordinate advances for concentration-camp survivors in Ukraine on the payments they receive as indemnification from Germany, and has so far assisted with hundreds of evacuations for Holocaust survivors to Israel, Poland, Moldova, and Germany. Meanwhile, the JDC set up two emergency hotlines staffed by Israelis who speak Russian and Ukrainian to facilitate evacuation inquiries and coordinate household-supply deliveries.

“Most of them do not want to leave, they’re not requesting evacuation,” says Deborah Joselow, chief planning officer for UJA, another organization that funds social services for survivors. “They said they lived through a war, and they would rather die in their own beds.”

Survivor Mitzvah Project, a nonprofit that has been working with Eastern European survivors since 2001, has helped 348 survivors across Ukraine, helping to coordinate deliveries of food, medical supplies, and firewood. Volunteers have reported Holocaust survivors taking refuge in bomb shelters and living in areas where pharmacies are closed and where they don’t feel safe going out to get food.

“We call them all of the time, and we call new ones every day to check on them and see how they’re doing,” says Zane Buzby, founder of the Los Angeles-based Survivor Mitzvah Project. “That’s a very important thing for them, to know they’re not alone and forgotten.”

In the U.S., social-services organizations have found that Holocaust survivors in their communities need special attention at this time as well. Staffers report that Holocaust survivors in general—especially those born in Ukraine—are finding news coverage of the war traumatizing.

“Survivors are reporting to us that they cannot sleep at night as the current war is bringing up severe trauma and triggering PTSD from their wartime experiences,” says Masha Pearl, executive director of The Blue Card, which provides food and financial assistance to Holocaust survivors on or below the poverty line. “They are terrified as they watch the news and are reminded of being sheltered from bombings. They are hounded by the painful memories of cold and starvation.”

In the Chicago suburb of Buffalo Grove, Khana Stolyar, 85, who lived in the Mogilev Podolskiy ghetto in western Ukraine during World War II, worries about relatives who have been living in Ukraine; her brother fled to Moldova after his house was bombed, and she talks to cousins on the phone who tell her they don’t have enough to eat. “When I hear of friends and family that are hungry,” Stolyar tells TIME through Maya Gumirov, who translated and works at CJE SeniorLife, which serves Holocaust survivors in the Chicago area, “it reminds me of being hungry during the war, and I’m heartbroken. It’s very scary.”

In Manhattan, Sami Steigmann, 82, who was born in what’s now the southwestern Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi and survived a labor camp, fears that World War III has already begun. He is afraid of “how far Putin is willing to go,” he says. “That really scares me.”

‘His gift is holy persistence’

On October 29, 2006, the New York Times published a heartbreaking story about enslaved children in in Africa.

It focused on Mark Kwadwo, an indentured 6-year-old — yes, you read that right — whose life on a fishing boat on Lake Volta in Ghana included work, beatings, the ever-present possibility of a deforming accident or even death, and absolutely nothing that had anything to do with childhood, except the benefits of having such a small, uncherished body to shove into small spaces.

Mark was one of many such children, sold into indenture or outright slavery by their parents, who could afford nothing else, or otherwise forced into labor.

Most people who read that story felt terrible. They — we — counted our blessings, felt pity, sympathized deeply, raged at injustice — and then we went on with our lives. There didn’t seem to be much else to do, anyway. Don’t we read stories of inhumanity all the time? Doesn’t madness lie in futile efforts to make a difference?

That’s not how Evan Robbins of Verona reacted. He helped free enslaved children, educate them, give them structure and love — and he also helped his students, back home in New Jersey, grow not only as students — that, after all, is a basic part of his job — but also as leaders and as people.

He’s straightforward, even matter-of-fact, when he tells his story.

“My younger child, Maya, was the same age as the boy in the story — she’s a senior in college now — and the differences between their lives just bothered me,” he said.

Mr. Robbins teaches AP government and U.S. history at Metuchen High school. “I brought the story to my students,” he said. He brought a speaker, Simon Deng, a human-rights advocate who had been enslaved as a child in Sudan, to his senior history class. “My students were moved,” he said. “We decided to do a walk in Metuchen to raise money. And that was the start of it.”

That first walk brought in $6,000.

The next year, there were more fundraisers; he was able to send $20,000 to help free trafficked children.

“And then, in 2010, I went to Ghana on a rescue mission” with the International Organization for Migration, a group that works with human trafficking, refugees, and internally displaced people, he said. He’d traveled widely before he met his wife, Lisa, and the two of them continued to explore the world together until his older daughter, Arianna, was born; “I’d been to Egypt, but this was my first time in sub-Saharan Africa.

“It was eye-opening.”

He landed in Accra, Ghana’s capital, and after a 13-hour drive the group — five people — arrived in Kete Krachi. They spent time on Lake Volta, talking to people they met, and then they went to a durbar — a traditional meeting. It’s a formal gathering, with rules. “You go around the circle the right way — I think it’s clockwise — and you shake everybody’s hand, and then you sit down, and then people make speeches, and then there is dancing, then a break, and then the meeting continues.” He wasn’t able to follow the discussion; it was in Ewe, the local language.

Children were being trafficked in this region, as they are in so many others around the world. The visitors wanted to talk about how it’s wrong, but that’s hard. “The roots of trafficking are poverty,” Mr. Robbins said. “People have too many children, and they have no money. There’s a history in Africa of sending a child you can’t take care of to a relative. This is a perversion of that.” Now, often, children are sold outright.

The group he was with in 2010 freed five children, four boys and one girl. They all were working on fishing boats. “The fishermen agreed to release them to us,” Mr. Robbins said. “We didn’t ever have an exchange of money. It was more persuasion.” What kind of arguments did the outsiders marshal? “I was an observer, but they would talk about how it is wrong, how you shouldn’t have children as slaves, how it is against the law.” Somehow, it worked.

“Once the children were released, we brought them to the hotel. The children went from having no expression, showing no emotion, to smiling and laughing.

“Children can be trafficked when they are as young as 4, 5, 6,” he continued. “There was a 6-year-old who had been there for years.”

The Ewe name their children after desirable attributes, and often those names are in English, Mr. Robbins said. He’s still in touch with two of those children, all these years later. Their names are Bright and Wisdom.

“Bright’s parents were separated; his father came back, said he wanted to take him for the summer, and sold him. His mom didn’t know where he was for five years. Wisdom was living with an elderly grandmother who couldn’t care for him, so she trafficked him.”

“They went to a rehab center after they were freed,” Mr. Robbins said, but after that there wasn’t much follow-up. Most of the nonprofit groups that freed enslaved children focused on that vitally important part of their mission. After two years at most, the liberated children were on their own. “Some are struggling, some are re-trafficked, some go back to their parents.” But if their parents had sold them in the first place, that reunion couldn’t be easy, and its outcome couldn’t be assured.

That first trip — he’s been back often, usually about once a year — convinced Mr. Robbins that he should start his own 501c3 organization. “I didn’t want to work through someone else,” he said. “I wanted to be able to raise more money, and to have more control over how it gets spent.” And he wanted to focus on long-term care.

To get there, he had to make a difficult choice, he said. He could focus either on numbers, helping to rescue many trafficked children, or he could use those same resources more intensely on fewer children.

The organization he created is called Breaking the Chain Through Education.

“So we hired a social worker, and then we decided to build a school. I read the book ‘Three Cups of Tea’” — a memoir about an American man who built schools for impoverished, education-deprived and -thirsty girls in Afghanistan and Pakistan — “and I decided that I would build a school in return for the release of 20 kids who had been trafficked.” The villagers had to commit to releasing children they had enslaved in order for the school to be built.

“And we built that school! I raised about $60,000 for a six-room school in 2012.”

About three years ago, Mr. Robbins opened an office in Ghana; it’s run by a staff he hired. “I fell in love with the children we care for, and I want to help them be better,” he said. “I always ask myself, ‘How can we do it better? How can we take it to the next level?’

“So now I have a staff of four people, and we agreed to take on 30 more kids, but not to do any more rescues or rehabs. I was just paying other people to do it, and I had no expertise in that. But I was able to help kids achieve long-term success through education and a trade. I know how to do that.

“When I was doing a rescue, I was just giving somebody money. I don’t have any expertise in that.”

So now he fundraises — last year, he raised about $280,000, he said — and uses the money for this long-term support.

“The rules are that we support them as long as they are moving toward independence,” Mr. Robbins said. “They have to be learning a trade, getting an education. Some of them now are almost 30. They lost so many years of their lives. We are trying to get them to be able to support themselves, to get out of poverty and be somewhere in the middle class.”

All of this comes from his Jewish values, Mr. Robbins said.

He and his family belong to Congregation Agudath Israel in Caldwell, and his daughters went to school at the Golda Och Academy in West Orange. “It’s hard to say which part of what I do comes from my Jewish values,” he said. “I can’t separate it out.” It’s entirely who he is.

“We are told that saving one life is like saving the world, but what does it mean to save a life?” he asked rhetorically. “Just getting them out of slavery, setting them free, wasn’t enough for me. You have to see them through.

“It’s a kind of universal value of love and care. The kids call me all the time. They call me Daddy. That’s a Ghanaian custom. It’s a sign of respect.

“When I see them after not seeing them for a year, they break into tears of joy. They have never had anyone care for them, or even be concerned about them.”

He recalled being in Ghana this summer. “We got together with the kids; we all had dinner in the office,” he said. “They all got up and talked. I said that I wanted them to be like a family to each other, to be there for each other. Their families had let them down, but they were there for each other.”

He told some success stories. “We set Bernice’s mother up in business, but it went under,” Mr. Robbins said. “And she made horrible decisions for her daughter. When Bernice was 16, her mother decided that she should live with a 34-year-old man, who impregnated her. Once we got her out of there, we put her up in her own house, and took care of her and her son.

“Now she’s about to start an apprenticeship as a beautician, and her son is 5, and in school; he’s the cutest kid you’ve ever seen. She made a speech about how appreciative she is.

“I’ve known her for 10 years. I saw her go through ups and downs, and now I’ve seen her coming into her own. It is so special.

“There’s Joshua, who kept getting kicked out of school, and now he’s going to be an electrician. So many of them have so much to overcome, and we let them figure it out. We stayed with them. Samson too will be an electrician; in May, they’ll both get their commercial licenses. To see them struggle, to be kids, and then to grow up and become mature people, who you’d be proud to call your son — that’s wonderful to see.

“We’ve stayed with them. It’s not always easy. But we tell the kids that if they’re not even trying to move forward, that we can’t take care of them anymore. But if they fix their act, they can come back.

“You have a part to play in it, too, we tell them. You have to work hard.”

So when he listens to them talk about their progress, he’s thrilled. “It validates your work,” he said.

Meanwhile, back in New Jersey, Mr. Robbins moved his nonprofit work from a class to a club. “I wanted the kids to be able to be involved in it for four years, not just for a semester or a year,” he said. “It’s by far the biggest club in the school; about 10 percent of the school comes to our weekly meetings.”

Students are involved with fundraising — there’s a big annual dinner, and a walk — and they also run the activities. “I guide them,” Mr. Robbins said. “We are doing a movie night for the elementary school; there’s a dance performance. The students designed a sweatshirt to sell as a fundraiser. One of the kids drew it. It’s a bulldog breaking chains.” Metuchen High School’s mascot is a bulldog. “And there’s a baking class, where they bake cookies; we charge parents to watch it.”

Students develop long-term relationships with the work they do with Breaking the Chain. “One of my former students now works at the State Department, and focuses on trafficking in Africa,” Mr. Robbins said. “She has made it her life’s work. I have a group of alumni students who now are young professionals in New Jersey and New York who work with me, who now come to the dinners as adults,” he added.

Breaking the Chain has started a sponsorship program; in return for sending money that supports a particular child, the sponsor can develop a relationship. “It’s a great bar or bat mitzvah project,” Mr. Robbins said. “The three co-presidents of the club now each support a kid. They send money they earn at after-school jobs.”

Rabbi Debra Orenstein leads Congregation B’nai Israel in Emerson; the focus of her social-justice work is freeing enslaved and trafficked people. She admires Mr. Robbins, with whom she has worked, immensely.

“What’s most remarkable to me about him is his perseverance and persistence,” she said. It’s not unusual to have been moved by the story in the Times that started his work. “People get these calls, this sense that there is an issue that is speaking to them. They might say, ‘Hey, somebody should do something about this.’ They might do something about it for a while. But it is very rare to have one of those moments, and then never to let go of it.

“It’s multigenerational at this point. There are adults out in the world now for whom this remains an important issue because they learned about it from Evan.

“And another part of his staying power is that he has maintained the school club. So much of what happens in schools goes in and out of fashion, in terms of what’s the popular club, or the cause that everyone has to support. But he’s kept on going, and that’s really rare.

“I think that his gift is holy persistence.

“His gift, the seventh of sephirot, is netzach.” Endurance. “It is a divine endurance.”

She first heard about Mr. Robbins when she read a story in the Jewish Standard in 2013 about a 13-year-old girl in Fair Lawn. That girl, Jessica Baer, had heard about Breaking the Chain when Mr. Robbins came to speak at her summer camp, Nah-Jee-Wah, in Milford, Pennsylvania, when she was 12. “For her bat mitzvah project, Jessica raised money for Evan’s organization. I wrote in Sharpie at the top of the story that ‘If a 12-year-old can do it, you can too.’” Rabbi Orenstein got in touch with Jessica’s father, Michael Baer, who also became deeply involved in Breaking the Chain, “and that led to more and more mitzvot,” she said.

Christina Le, who graduated from Metuchen in 2008, first knew Mr. Robbins as a teacher, before he started to work with trafficked children. When she was a senior, she was in the first class he taught after he’d gotten involved with Ghana. “Mr. Robbins is one of the most incredible human beings you could ever come across,” she said. “The funny thing is that I still call him Mr. Robbins, out of respect. The level of inspiration and caring that he brings to others — even in high school, he was able to get us to the point of really caring, to actually working on this project.

“He inspired us on history alone, and that is a rare thing,” she said. She took U.S. history with him, and then she and her cousin both “took a model Congress class with him. We cared nothing about the law, but we took it because he was teaching it.”

That was the first year that Mr. Robbins brought his social justice work in Ghana to school, and Ms. Le and her friends joined it enthusiastically. “That first year, raising money, doing walks, we were able to save 10 kids,” she said. She’s stayed in touch with Mr. Robbins and with Breaking the Chain. “He has done an incredible job,” she said.

Ms. Le now works in wholesale fashion; one of the lessons Mr. Robbins taught was that help and support can come from anywhere. You just have to be creative. “I can get a ton of samples, and we can sell them, get some money, and send the money over to Ghana — it’s cheaper to buy clothing there than it is to ship it from here,” she said.

She has a network of friends who all fundraise for Breaking the Chain and spread the word about its work.

“To see acts of kindness at the level that Mr. Robbins does them is so rare,” she said.

One of his gifts as a teacher is his charisma, she added. “He is so funny, and he’d always bring great stories.” The traveling that he’s done, and the experiences he’s had, allow him to bring a wider perspective to his students. “He understood that putting us in another person’s shoes made it easier to understand that other person.

“And he is so full of energy. Even when a kid did something wrong, he always was there. He was emotionally supportive. He was our high-school dad, and we loved him so much.

“After we graduated, he was always the person we went back to high school to visit. We’d see other people too, but he was the one we went to see.”

Brooke Margolin was a president of the Breaking the Chains club when she was at Metuchen High School; now she’s a senior at Rutgers.

She met Mr. Robbins when she was in middle school, she said; she was a dancer, and performed at a Breaking the Chains benefit with her studio, the Metuchen Dance Center.

When she was in 10th grade, she joined the club. “I’d thought about doing it before, but I finally went then,” she said. As he always did, Mr. Robbins started talking about his work in Ghana, and she was hooked.

She became active in the club; by her junior year, she was a vice president. She continued to dance at the benefit, and she started some other fundraising activities, including a tricky tray auction. She had twin sisters, Julianna and Rebecca, who were a few years below her in school; they too joined the club. “And then we had the great opportunity to go to Ghana with Mr. Robbins,” she said.

It was 2017, the summer before her senior year, and she was set to become president. She, her sisters, and her father, Josh, and Jessica Baer and her father, Michael, who’d become a member of the board of Breaking the Chain, went to Ghana together.

They spent about a week there. “We met a significant number of children, and it was a fascinating experience,” Ms. Margolin said. “He went in depth with every child. It was the same protocol for every child; we’d meet with the principal and the teacher, we’d drive to the school, go into their classroom, meet the child and play with them, and then go back to the home and meet the parent or caretaker. We took notes; we discussed the child’s performance in their school, and their mental, social, physical, and emotional well-being.”

Those Ghanaian children ranged in age, but “every one of them had been rescued, and every one of them had a different story,” Ms. Margolin said. “Some lived with their parents. One of them who we met, who Evan considers to be a poster child for the organization, lived with her teacher, and applied for university. It was eye-opening.

“We got to really cut through some of the trauma they had faced, and we had the great fortune to get to know them as people. Take away that they were formerly trafficked children — we had to forge relationships.”

Language could be a barrier, but they overcame it, she said. “Lizzie, who was the one who had lived with her schoolteacher, she always loved dancing. We had a show, and my sisters and I performed an American tap routine, and Lizzie had some members of her community do a dance for us.

“We were able to communicate beyond the language barrier. We found other ways to get to know each other.”

Mr. Robbins’ work has had a lasting effect on Ms. Margolin. “I am majoring in public health, with certificates in global health and health policy and health disparities, and I’m also getting an MPH in epidemiology. One hundred percent I wouldn’t have done that without that trip.

“When we were in Ghana, many of the people we were with, including my sisters and my dad, all focused on the child well-being and education aspect, but my focus was drawn a little more toward innovative solutions to increasing sanitization, to focusing on getting clean water, and on food safety and disease control.

“I remember seeing students at their school turning over a gallon milk bottle with a pulley system, where they’d step on a piece of wood and that would tip the bottle and water would pour out. That’s how they washed their hands.”

Ms. Margolin also knows that she learned some pragmatic, transferable skills from Mr. Robbins. “Planning, organizing campaigns, drafting grant proposals, all these advanced skills that you tend to learn when you are getting an advanced degree — I had the opportunity to learn it in high school.

“To this day, Evan and I joke about how we are opposites. He is very laissez faire. He has a big picture that he wants you to achieve. And I am the opposite. I have a tendency to micromanage. I really like every detail to be perfect.

“That created an interesting dynamic. He was the club advisor, with all this information, and the relationships that he had built, and he was able to say, ‘This is what I want to do.’ And I was able to raise x amount of dollars, and say, ‘This is where it will go. This is how we will allocate it.’ So we had the before — this is what I want — and the after — this is what we did.”

Ms. Margolin is Jewish — she and her family belong to Congregation Neve Shalom in Metuchen — and “I definitely see a connection between Jewish values, particularly of tzedakah, and our work in the club,” she said. “I went to preschool at Neve Shalom, and for Hebrew school, and I remember that before every class in Hebrew school, we would start with the tzedakah jar in the front of the class. Every student had their bag of change, and we’d put it in, and we’d always talk about where the money was going, and about the importance of giving back to your community, and helping those not in the same position as you.”

Sophie Lunt is a senior at Metuchen High School, and she’s one of the three Breaking the Chain co-presidents this school year.

She joined the club “because it was the biggest club in the school, and a lot of my friends were joining it,” she said. It was a fairly cold entrée, but her relationship to it heated up quickly. “I do dance, and I just thought that it was really cool how dance was making a difference for children in Ghana.” The club continues to offer a dance performance as a fundraiser, as it has since it began. “There was nothing comparable to it anywhere else in the school.”

Ms. Lunt plans to continue to join clubs like Breaking the Chain when she’s in college, and “after college, depending on what happens, I actually will volunteer for it. I think it’s a really good way to keep in touch with everything that’s going on.”

She sponsors a child. “It’s new this year,” she said. “You can pitch in whatever amount you want monthly, and that goes to one specific child. You can email them.

“I had the privilege of speaking on the phone to my child, who I believe is 20. She has a daughter. She just passed her exams and she is going on to pick a university. We talked about how we are in the same position right now, and it is really cool, being able to be in touch with someone and see the tangible effects of your contribution.

“Breaking the Chain is just truly amazing,” Ms. Lunt concluded. “Mr. Robbins — everything he does is out of this world. It’s amazing, how much effort he puts in, and everything he does for those kids.

“I take a history class with him. He’s an engaging teacher. He doesn’t like to teach from a textbook. He’s just really amazing.”

Learn more about Breaking the Chain Through Education at www.btcte.org.

Good people make good neighbors … and good funds

During tough times, the world relies on people and organizations committed to doing good. In fact, that’s true even when the world is doing well. To that end, Naomi Eisenberger and the Good People Fund are dedicated to serving others in the United States, in Israel and throughout the world.

Executive director Naomi Eisenberger, 76, is no stranger to helping others. Indeed, the Good People Fund is inspired by ordinary people with an extraordinary drive to make deep, uplifting impacts in communities in the United States, Israel and elsewhere around the world, trying to find new and creative ways to address seemingly intractable social and economic challenges. It is her second major venture in this field after a career that includes being a high school history teacher, kosher caterer and part of a family retail business.

Eisenberger and the fund keep costs down so they can serve those in need. She reports that her office is the bedroom of her home in a New Jersey suburb, though she notes that “we do have a separate phone line.”

“We are a ‘little known fund, not a foundation,’ ” she says. “We are not your typical nonprofit organization.”

She is quick to add that “what goes in goes out.”

Eisenberger was turned on to the world of tzedakah and charitable giving very much by accident. “Around 1991, I was becoming shul president of Congregation B’nai Israel in Milburn, New Jersey. Just before a family vacation, I was meeting with our rabbi, Steve Bayar, and was looking at the books on his shelf. I told him I needed something else to read. He handed me Gym Shoes and Irises: Personalized Tzedakah [Book 1, published in 1981] and Book 2 [published in 1987].”

Eisenberger is referring to two of the many books written by Danny Siegel, founder of the Ziv Tzedakah Fund who travels the country and the world speaking about the value of giving.

Siegel founded his fund in 1981 after making several trips to Israel and serving as a shaliach mitzvah—one who brings money for distribution to those in need. On subsequent trips, he asked friends and relatives for a dollar or two to give as charity.

He went in search of “good people” he called “Mitzvah Heroes.” These heroes were actually regular Israelis quietly working to make the world a better place through their actions.

Prior to the meeting in Bayar’s study, Eisenberger hadn’t heard of Siegel. She read both books on her vacation and was hooked. “I am totally enthralled,” she told Bayar upon her return. And she had an idea. “I am being installed in June. Let’s bring Danny Siegel as a scholar and use him to found our shul’s chesed committee.”

‘Inspired by life experiences’

Eisenberger and Siegel immediately hit it off during his weekend at the synagogue. In addition to his talks in the synagogue, Siegel spoke at a small Saturday-evening gathering in her home. The idea for a “Hearts and Hands” committee was born.

“He challenged us,” recalls Eisenberger. “If you have extra Torahs in your shul, halachah [Jewish law] is that you can sell it for the purpose of tzedakah.”

Eisenberger was inspired and motivated. “I never back away from a challenge. I convinced the board. We sold TWO Torahs, and this became our endowment so we could allocate funds in Israel, in the United States and locally.”

Eisenbeger kept in touch with Siegel. Soon after, he asked her to do some volunteer work with the Ziv Fund. He and Ziv were badly in need of an administrator. Flattered and interested, she traveled to Rockville, Md., to meet with Siegel. Eisenberger returned to New Jersey with boxes of records, opened an account and served as a volunteer administrator for nearly three years.

Over time, Eisenberger needed paid employment. She eventually convinced Siegel to hire her. Eisenberger served as managing director of the Ziv Tzedakah Fund for more than 10 years.

The fund reportedly gave away more than $14 million in its 32 years of operation—mainly to small, innovative programs and projects in Israel and America that needed assistance—before Siegel and the board decided to close it down in 2008.

Nonetheless, Eisenberger was determined to continue doing mitzvah work: “I said, ‘I’m starting over; this is too important!”

“Having met and worked with Danny, I discovered a whole different philosophy and way to look at the world and life,” reports Eisenberger, who started the Good People Fund in that same year, 2008, to provide financial support and management guidance to small and mid-sized nonprofits committed to tikkun olam, “the repair of the world.”

The fund currently supports programs in 15 states, Israel and countries in Eastern Europe, Africa and India. While the majority of programs are not run by Jewish people, Eisenberger says they are all “based on Judaism” and Jewish principles. And the fund finds them on its own; it does not take proposals.

Another characteristic of all grantees, adds Eisenberger, is that “most have been inspired by their own life experiences.” She playfully notes an additional shared feature: “Very few have studied or know the first thing about nonprofit management; this is an additional reason our work with them is so important.”

It is this latter role that distinguishes Good People from other funders. “Our ability to offer mentorship is a significant and unique part of our work,” she said, “and it makes all the difference in the world!”

Eisenberger has a knack for identifying organizations in their very early stages when they need the greatest support. “I have a well-cultivated gut. After 25 years, I know it when I see it. I am looking for people with drive, passion, visionaries without any sense of ego—all selfless people.

And she has found people doing good and important work in such diverse areas as elder care, fighting hatred, healing broken communities, health and well-being, human needs and self-sufficiency, hunger and food rescue, inclusion and disabilities, kids, poverty and fundamental needs, refugees and women’s empowerment. Eisenberger says she cares deeply each grantee: “They drive me—they inspire me!”

He went in search of “good people” he called “Mitzvah Heroes.” These heroes were actually regular Israelis quietly working to make the world a better place through their actions.

Prior to the meeting in Bayar’s study, Eisenberger hadn’t heard of Siegel. She read both books on her vacation and was hooked. “I am totally enthralled,” she told Bayar upon her return. And she had an idea. “I am being installed in June. Let’s bring Danny Siegel as a scholar and use him to found our shul’s chesed committee.”

‘Inspired by life experiences’

Eisenberger and Siegel immediately hit it off during his weekend at the synagogue. In addition to his talks in the synagogue, Siegel spoke at a small Saturday-evening gathering in her home. The idea for a “Hearts and Hands” committee was born.

“He challenged us,” recalls Eisenberger. “If you have extra Torahs in your shul, halachah [Jewish law] is that you can sell it for the purpose of tzedakah.”

Eisenberger was inspired and motivated. “I never back away from a challenge. I convinced the board. We sold TWO Torahs, and this became our endowment so we could allocate funds in Israel, in the United States and locally.”

Eisenbeger kept in touch with Siegel. Soon after, he asked her to do some volunteer work with the Ziv Fund. He and Ziv were badly in need of an administrator. Flattered and interested, she traveled to Rockville, Md., to meet with Siegel. Eisenberger returned to New Jersey with boxes of records, opened an account and served as a volunteer administrator for nearly three years.

Over time, Eisenberger needed paid employment. She eventually convinced Siegel to hire her. Eisenberger served as managing director of the Ziv Tzedakah Fund for more than 10 years.

The fund reportedly gave away more than $14 million in its 32 years of operation—mainly to small, innovative programs and projects in Israel and America that needed assistance—before Siegel and the board decided to close it down in 2008.

Nonetheless, Eisenberger was determined to continue doing mitzvah work: “I said, ‘I’m starting over; this is too important!”

“Having met and worked with Danny, I discovered a whole different philosophy and way to look at the world and life,” reports Eisenberger, who started the Good People Fund in that same year, 2008, to provide financial support and management guidance to small and mid-sized nonprofits committed to tikkun olam, “the repair of the world.”

The fund currently supports programs in 15 states, Israel and countries in Eastern Europe, Africa and India. While the majority of programs are not run by Jewish people, Eisenberger says they are all “based on Judaism” and Jewish principles. And the fund finds them on its own; it does not take proposals.

Another characteristic of all grantees, adds Eisenberger, is that “most have been inspired by their own life experiences.” She playfully notes an additional shared feature: “Very few have studied or know the first thing about nonprofit management; this is an additional reason our work with them is so important.”

It is this latter role that distinguishes Good People from other funders. “Our ability to offer mentorship is a significant and unique part of our work,” she said, “and it makes all the difference in the world!”

Eisenberger has a knack for identifying organizations in their very early stages when they need the greatest support. “I have a well-cultivated gut. After 25 years, I know it when I see it. I am looking for people with drive, passion, visionaries without any sense of ego—all selfless people.

And she has found people doing good and important work in such diverse areas as elder care, fighting hatred, healing broken communities, health and well-being, human needs and self-sufficiency, hunger and food rescue, inclusion and disabilities, kids, poverty and fundamental needs, refugees and women’s empowerment. Eisenberger says she cares deeply each grantee: “They drive me—they inspire me!”

He went in search of “good people” he called “Mitzvah Heroes.” These heroes were actually regular Israelis quietly working to make the world a better place through their actions.

Prior to the meeting in Bayar’s study, Eisenberger hadn’t heard of Siegel. She read both books on her vacation and was hooked. “I am totally enthralled,” she told Bayar upon her return. And she had an idea. “I am being installed in June. Let’s bring Danny Siegel as a scholar and use him to found our shul’s chesed committee.”

‘Inspired by life experiences’

Eisenberger and Siegel immediately hit it off during his weekend at the synagogue. In addition to his talks in the synagogue, Siegel spoke at a small Saturday-evening gathering in her home. The idea for a “Hearts and Hands” committee was born.

“He challenged us,” recalls Eisenberger. “If you have extra Torahs in your shul, halachah [Jewish law] is that you can sell it for the purpose of tzedakah.”

Eisenberger was inspired and motivated. “I never back away from a challenge. I convinced the board. We sold TWO Torahs, and this became our endowment so we could allocate funds in Israel, in the United States and locally.”

Eisenbeger kept in touch with Siegel. Soon after, he asked her to do some volunteer work with the Ziv Fund. He and Ziv were badly in need of an administrator. Flattered and interested, she traveled to Rockville, Md., to meet with Siegel. Eisenberger returned to New Jersey with boxes of records, opened an account and served as a volunteer administrator for nearly three years.

Over time, Eisenberger needed paid employment. She eventually convinced Siegel to hire her. Eisenberger served as managing director of the Ziv Tzedakah Fund for more than 10 years.

The fund reportedly gave away more than $14 million in its 32 years of operation—mainly to small, innovative programs and projects in Israel and America that needed assistance—before Siegel and the board decided to close it down in 2008.

Nonetheless, Eisenberger was determined to continue doing mitzvah work: “I said, ‘I’m starting over; this is too important!”

“Having met and worked with Danny, I discovered a whole different philosophy and way to look at the world and life,” reports Eisenberger, who started the Good People Fund in that same year, 2008, to provide financial support and management guidance to small and mid-sized nonprofits committed to tikkun olam, “the repair of the world.”

The fund currently supports programs in 15 states, Israel and countries in Eastern Europe, Africa and India. While the majority of programs are not run by Jewish people, Eisenberger says they are all “based on Judaism” and Jewish principles. And the fund finds them on its own; it does not take proposals.

Another characteristic of all grantees, adds Eisenberger, is that “most have been inspired by their own life experiences.” She playfully notes an additional shared feature: “Very few have studied or know the first thing about nonprofit management; this is an additional reason our work with them is so important.”

It is this latter role that distinguishes Good People from other funders. “Our ability to offer mentorship is a significant and unique part of our work,” she said, “and it makes all the difference in the world!”

Eisenberger has a knack for identifying organizations in their very early stages when they need the greatest support. “I have a well-cultivated gut. After 25 years, I know it when I see it. I am looking for people with drive, passion, visionaries without any sense of ego—all selfless people.

And she has found people doing good and important work in such diverse areas as elder care, fighting hatred, healing broken communities, health and well-being, human needs and self-sufficiency, hunger and food rescue, inclusion and disabilities, kids, poverty and fundamental needs, refugees and women’s empowerment. Eisenberger says she cares deeply each grantee: “They drive me—they inspire me!”

‘The inner strength of people’

The warm feelings and admiration are mutual.

Yoni Yefet Reich, the co-founder of Amutat Beit Zayin in Israel, met Eisenberger more than a decade ago in Israel. “From my first interaction, I immediately recognized that she was a different type of funder representing a different kind of collective. She clearly understood the issues at hand and was an ‘out-of-the-box’ strategist.”

He and his team wanted to develop Kaima Farms—a socially responsible education network that many others deemed untenable. Fast-forward and today, Be’erotayim is one of five Kaima farms where youth are responsible for planting, nurturing and harvesting crops and for running a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) venture. Other farm communities include Kaima Nahalal, focused on helping young girls, including many who have experienced sexual trauma and have not succeeded in more traditional educational settings.

Reich says “we count ourselves fortunate to receive not only funding, but friendship and professional guidance that have helped us develop from a single youth-run, CSA operating farm into a network of four in Israel and one in Tanzania. Our unfolding story would simply not be possible without the involvement of the fund, and, of course, Naomi.”

“If there are 36 hidden tzadikim,” as Jewish tradition implies, she insists that “Naomi is certainly one of them, hiding in plain sight.”

Fraidy Reiss, founder and executive director of Unchained at Last—an organization leading the effort to make child marriage illegal in the United States—is herself a survivor of an arranged marriage. As such, she works to help those who are victims of child or forced marriage by providing them with legal and social services.

She says she is appreciative of Eisenberger’s support and her style: “What is special is that she became an ally, a mentor and more.”

Reiss notes that “starting a nonprofit is a lonely and daunting journey; you need someone to be a sounding board.”

On her part, Eisenberger says she continues to learn and be moved by each person and entity: “One of the lessons I’ve learned is the strength of people—the inner strength of people is something to marvel.”